Chris Schwarz went off to England and France this summer and saw some tools. I went to New Jersey.

Rare books rooms are different than regular libraries' reading rooms. They are the holy of holies of the printed word where the most valuable and fragile possessions of a library collection are studied. At Princeton University, the rare book room is segregated from the rest of the library, It's fairly small, but the room is windowed, airy, and comfortable. A librarian on constant duty sits at a desk in the front of the room. The librarians are deeply concerned with making sure the collection stays put, is treated well, and isn't damaged. Before I was allowed in, I needed to sign in, get a badge, request what I want to see, and then put all my stuff I brought, including my notebook, in the closet. After all that, I had to wash my hands. Only then could I go into the rare book reading room.

I was ushered to an oak desk with a green table light, and most important for scholarship, a comfy chair. To prevent ink spills, smudges, and absent-minded scholars indelibly scrawling "So true! So true!" in the margins of a four hundred year old book, pens of any kind are forbidden. The reading room does supply paper and pencils, though - presumably because pencil can be erased. The seats were full of people sitting and reading, occasionally writing notes on the supplied paper or typing something on laptop computers. This is where scholarship finds its roots - original sources.

I had traveled to see a tool catalog from 1869. The curator thought Princeton had one of perhaps two surviving copies; the other one, if it exists, is in a collection in Europe. The catalog consists of two items and after a short wait, the book with the plate descriptions was brought to me and set up on wedges so that it could lie open enough to read without straining the binding. The plate of the catalog are separate and are about 18" x 24" and so big they were just laid flat on the table.

Most of the time, when I see a rare book for work I am doing, the experience is anticlimactic. Even when it's fascinating, informative, and new to me, it's still a book and doesn't appreciate the 3 hours I spent coming to visit it. This catalog was different. I was stunned. I have never seen a catalog so beautiful and impressive.

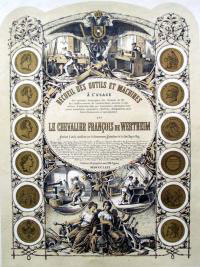

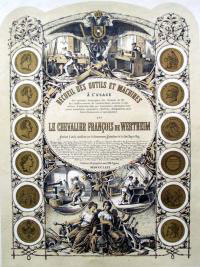

The Handbook of the Tools of Arts and Industry: For the Use of Technical Schools, Railroad Companies, and Navigation was published in 1869. The company that published the catalog, Franz Freiherr von Wertheim, was based in Vienna, but the catalog is in French. This is because it isn't a typical catalog for local hardware stores. The plates were printed big, and the paper is heavy and high quality, for display originally at Paris Exposition of 1867. There about 45 plates, of which about half are in delicious, detailed, lithographed color. The display of tools shown above is the only double sized plate and it is incredible in it's level of detail. The company won early awards in steel manufacture which is probably reflected by the large number of blades in the center of the display. Aside from those blades, many pages of the catalog are given over to various edge tools, including turning tools of a very specialist nature which the company presumably made. However, overall the tools shown throughout the catalog seem solidly mid-tier, neither top-of-the-line nor cheap, and in a wide range, including some English and American tools with the majority Continental. All of these factors suggest that while Wertheim did manufacturer edge tools, it was a large company and the catalog represents a division that mostly functioned as a distributor of tools, rather than a manufacturer.

Nineteenth century color tool catalogs are rare. I only know of two others (and one off those was hand colored). This Wertheim catalog is in wonderful shape, and its color and level of detail are just awesome. However, what I really took away with me is information about the tools themselves. There were a couple of tools in the catalog that stumped me - I am not sure of what they are. I need to do some more translating of the book of descriptions. And there were several tools that have completely disappeared and are not even listed in Salaman's Dictionary of Woodworking Tools. I found a new style of a kind of lock mortise chisel that might be easier use for leveling the bottom of mortises, a couple of very interesting lathe tools, and a few gadgets that all bear further research. I think you will be seeing new tools informed by the catalog in the coming years. Nineteenth century color tool catalogs are rare. I only know of two others (and one off those was hand colored). This Wertheim catalog is in wonderful shape, and its color and level of detail are just awesome. However, what I really took away with me is information about the tools themselves. There were a couple of tools in the catalog that stumped me - I am not sure of what they are. I need to do some more translating of the book of descriptions. And there were several tools that have completely disappeared and are not even listed in Salaman's Dictionary of Woodworking Tools. I found a new style of a kind of lock mortise chisel that might be easier use for leveling the bottom of mortises, a couple of very interesting lathe tools, and a few gadgets that all bear further research. I think you will be seeing new tools informed by the catalog in the coming years.

In addition there were tons of plane profiles that I haven't seen in other catalogs and I think really just reflect the fancier furniture styles of the continent.

While the catalog does contain a foot powered hand mortising machine and a treadle table saw, there is a stress on hand tools, many highly specific for production work that by this time have disappeared from American and English catalogs. A contemporary American tool catalog would have been filled mostly with stationary, cast iron machines that this catalog doesn't contain. It could be that there was no demand for their target audience, as specified by the title of the catalog, but in general the catalog seems twenty or thirty years behind what the American were selling. There is a lot to be studied and learned here.

I was allowed to photograph the catalog, which I did, but as a condition of the permission I am not allowed to publish the pictures, which is why I haven't included any here. I did ask about getting the catalog reprinted, or getting it scanned for an electronic version. This would be absolutely wonderful and I am hoping it happens soon. I would also like to thank Julie Mellby, the librarian of the Graphic Arts Library, who was responsible for acquiring the catalog, for being so helpful and welcoming to me.

I learned about the catalog from my friend Jeff Peachy, who pointed me in the direction of the Graphic Arts Blog at Princeton. For more information you can read the entry on the tools here, and it is where the plates shown in this blog entry come from. I learned about the catalog from my friend Jeff Peachy, who pointed me in the direction of the Graphic Arts Blog at Princeton. For more information you can read the entry on the tools here, and it is where the plates shown in this blog entry come from.

My next step in all of this is to digest the information and look up some stuff, especially on early turning tools. Then comes the fun part, making some prototype tools and seeing if they work, or if they vanished because they didn't really work, or maybe because the work they were used for stopped being commercially important.

|

Joel's Blog

Joel's Blog Built-It Blog

Built-It Blog Video Roundup

Video Roundup Classes & Events

Classes & Events Work Magazine

Work Magazine

Nineteenth century color tool catalogs are rare. I only know of two others (and one off those was hand colored). This Wertheim catalog is in wonderful shape, and its color and level of detail are just awesome. However, what I really took away with me is information about the tools themselves. There were a couple of tools in the catalog that stumped me - I am not sure of what they are. I need to do some more translating of the book of descriptions. And there were several tools that have completely disappeared and are not even listed in Salaman's Dictionary of Woodworking Tools. I found a new style of a kind of lock mortise chisel that might be easier use for leveling the bottom of mortises, a couple of very interesting lathe tools, and a few gadgets that all bear further research. I think you will be seeing new tools informed by the catalog in the coming years.

Nineteenth century color tool catalogs are rare. I only know of two others (and one off those was hand colored). This Wertheim catalog is in wonderful shape, and its color and level of detail are just awesome. However, what I really took away with me is information about the tools themselves. There were a couple of tools in the catalog that stumped me - I am not sure of what they are. I need to do some more translating of the book of descriptions. And there were several tools that have completely disappeared and are not even listed in Salaman's Dictionary of Woodworking Tools. I found a new style of a kind of lock mortise chisel that might be easier use for leveling the bottom of mortises, a couple of very interesting lathe tools, and a few gadgets that all bear further research. I think you will be seeing new tools informed by the catalog in the coming years.  I learned about the catalog from my friend

I learned about the catalog from my friend

Thank you.

The Wertheim tools exhibited in Paris in 1867 were sold to the South Kensington Museum in London. It may be worth a try to find out if they still have them. I know, because I have seen them, that his tools from the 1855 Paris exhibition, are in the CNAM museum in Paris.

As I wrote over at WoodCentral I have a digital copy of the German edition. There are at least five copies of this book in German and Austrian libraries and private collections I know of. If I can be of any help regarding tools, the history of Wertheim or with translation please let me know.

Wolfgang

Gary